Hi, My Name Is Dalton and I’m a Time Trouble Addict

A personal deep-dive into a chess player’s most common (and most frustrating) weakness

Hi, my name is Dalton and I’m a time trouble addict.

This isn’t a twelve-step meeting but it probably should be. Because if there’s one recurring problem in my chess career, it’s not my openings, or my tactics, or even my nerves. It’s my inability to move.

I’ve lost more games to the clock than I’d like to admit. Some of them were equal. Some of them were better. All of them hurt in a way that’s hard to describe unless you’ve sat there, one move away from the second time control, watching your flag fall.

This is going to be a long post. I don’t have the definitive answer to solving time trouble. I still fight it every tournament. But I want to put this down as a kind of diary entry. A record of what I’ve tried, what I’ve learned and what has and hasn’t seemed to work. Maybe it’ll help someone else. Maybe it’ll just remind me to move my hand faster next time.

Why Time Management Actually Matters

Everyone knows time management is important but I don’t think most players (including myself) internalize how directly it affects results. You can be the best player in the room but if you’re under a minute every game, you’ll never get to show it.

Julian from Chess Engine Lab wrote an excellent post showing some of the stats and data regarding how being low on time contributes to more mistakes.

You can have all the positional understanding in the world but it won’t matter if you’re trying to find “the only move” with five seconds left.

My Personal History with Time Trouble

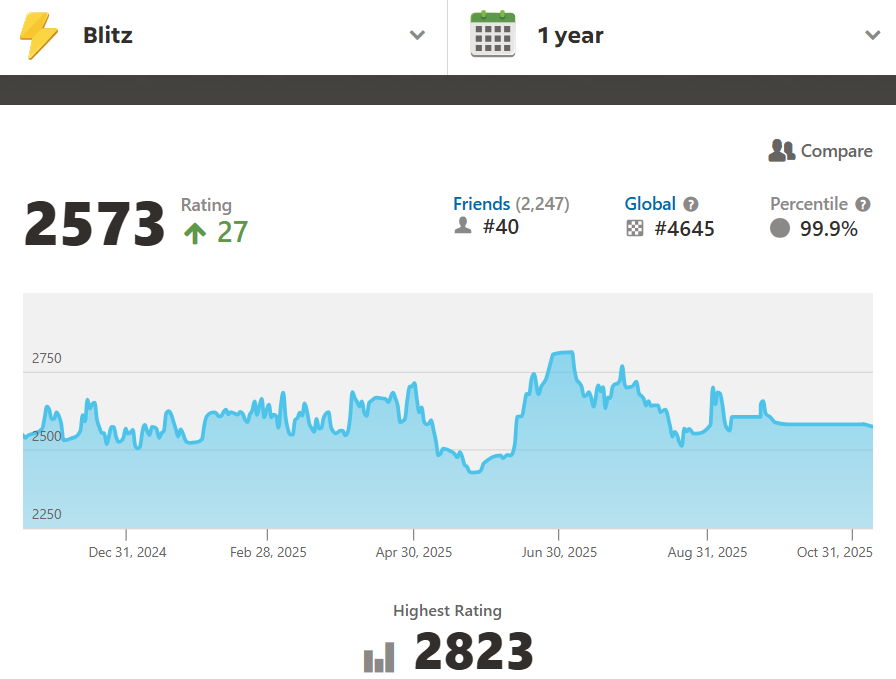

I’ve been decent at blitz for years. My online blitz rating generally hovers around 2550-2600 and I’ve peaked over 2800.

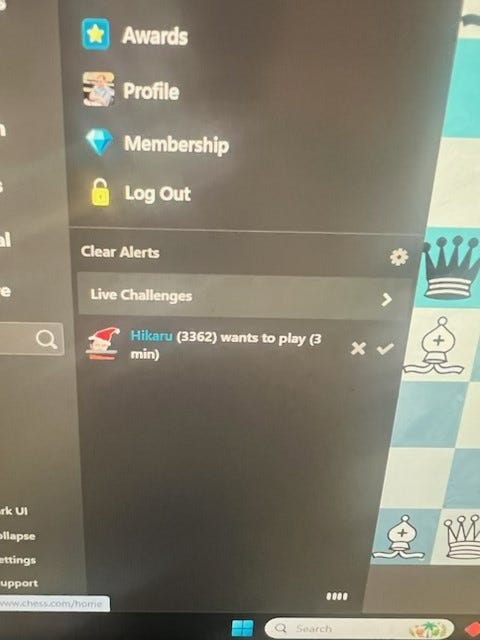

Hikaru even challenged me a few times to try to farm my rating points back then. The only reason he didn’t get to farm me was because I was busy teaching lessons at that time, or at least that’s what I tell myself 😉

Anyways, that’s strong enough to prove to myself that I can move fast when I need to. But in OTB tournaments, everything changes. The stakes feel higher and the clock more intimidating.

The worst example came in the final round of the recent Midwest Class Championship. I was playing White against one of the strongest nine-year-olds in the country, rated around 2100 USCF. We reached an endgame around move 35 where I had a pleasant advantage. Then on move 39 he played a move (…Bh5) that surprised me. I froze.

On move 40, I thought too long. I played my move (Kg3) right as my flag fell. Had I moved a few seconds faster, I would have gained another half hour and probably gone on to win (or at least draw). Instead, I lost on time. A decent tournament ended on a sour note.

That moment replayed in my head for days. Not because I made a mistake on the board but because I never even got the chance to.

During tournaments, I always write how much time each player has after every move on my scoresheet. I also put a small dot next to the moves where I know I spent too long thinking. After games, I review it like a forensic report. It’s humbling to see how early the pattern starts. Move 10, 12, 14. The slow bleed begins long before any critical moment. There are a lot of dots on my scoresheets.

A former coach once told me, “Every time you overthink a move, imagine paying me $10.” It was his way of putting a price on indecision. I should owe him a few hundred dollars by now.

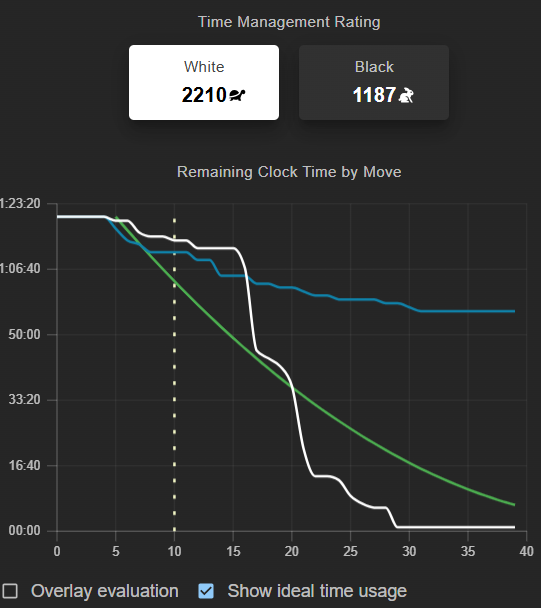

I’ve even used the ChessDojo time management graph to visualize how bad it gets. Seeing it plotted in real time was a wake-up call.

I’m going to assume my opponent’s time management rating is so low because he played “too fast” and still had 56 minutes on his clock at the end of the game. That doesn’t matter when I end up flagging though.

Kids don’t seem to worry about playing perfect chess and just play decent moves quickly. In that way, I wish I was a kid again.

The ADHD and Perfectionism Problem

I was diagnosed with ADHD years ago, and one of the defining traits is what’s called “time blindness.” My perception of time is unreliable. In real life, that means I’m often late. In chess, it means I lose track of how long I’ve been thinking.

That alone would be manageable. The real issue is how it interacts with my perfectionism. I want to find the “right” move. I want to avoid regret. The idea of playing a move that might be slightly wrong feels unbearable.

Part of that comes from how I view my own defensive ability. I don’t think I’m great at saving bad positions. So I subconsciously treat every decision as life or death, as if one imperfect move means immediate defeat. That mindset is poisonous for time management.

What I’ve Learned from Smarter People

I’m far from the first player to struggle with this. It’s comforting to know I’m in good company.

In Seven Deadly Chess Sins, Jonathan Rowson devotes an entire section of the book to perfectionism (section 6) and a full chapter within that section to poor time management: “The Causes of Time-Trouble (and a few remedies)”. He says “what is important is that you realize just how important a part of the game the clock is, and…it may be helpful to see it as one of the four dimensions of the game, to be treated with as much attention as the other three”.

GM Gregory Kaidanov once gave me several practical pieces of advice that have stuck with me:

When you can’t decide between two or three good moves, it usually means they’re about equal. Just play one.

The fate of the game is often decided between moves 20 and 30, so save your time for then. Play faster early.

There’s no correlation between how long you think and how good your move is. You can spend 20 minutes and still play a blunder.

If your position is worse, thinking forever won’t make it better. Pick a move and play it. The time you save might save the game later.

The critical moments are usually trades or pawn structure changes. Save your time for those.

When you find yourself staring at a move that doesn’t work but can’t let it go, move on. Don’t waste energy trying to prove reality wrong.

Junta Ikeda has written some excellent posts on time trouble:

Nate Solon’s piece on Zwischenzug, simply titled “Time Management”, also captures the psychological battle perfectly.

All of these make one thing clear: Time management isn’t a technical issue. It’s an emotional one.

My Experiments in Breaking the Addiction

I’ve tried just about everything to fix this.

1. Chrome Extension

I installed a Chrome extension where GothamChess or Hikaru would yell at me if I spent too long on a move. It’s ridiculous, but it works. A quick “MOVE!” from Hikaru can jolt you out of your perfectionist trance. Unfortunately this extension is no longer available but was fun while it lasted.

2. Background Interval Timer

Sometimes I play blitz with a five or ten-second interval timer playing (loudly) in a YouTube tab. It forces rhythm. Like a metronome for decision-making.

3. Shot Clock Chess

This one’s my favorite. I play “shot clock” training games with friends where we must move every 30 seconds or less. I get three “extensions” per game where I can think longer. It’s based on the NBA and poker shot clock systems. You can’t tank forever. You have to act.

4. Timed Calculation Drills

For puzzles or calculation exercises, I set a timer that limits my think time per move. This isn’t my main weakness, but it reinforces the habit of committing instead of staring.

5. Guess-the-Move Training

I’ll watch a strong player’s blitz game and pause at every move to guess what they’ll play. I compare my intuition instantly, not after deep thought. It trains snap recognition. You can also do this with longer games as I did with Nate Solon a few weeks ago.

6. Randomized Decisions

Borrowed from poker. If I have two moves that both look fine, I essentially flip a coin (in practice games). Heads, move A. Tails, move B. It sounds absurd, but it helps me break the paralysis of choice.

Each of these has helped a little. None have cured the problem entirely. But together, they’ve built awareness, and awareness is step one in recovery.

Principles I’m Trying to Live By

If you can’t decide, both moves are probably fine.

Play faster in the opening and early middlegame. Save time for complexity later.

Trust your intuition. You built it through years of study.

Accept that mistakes are inevitable. Time trouble guarantees more of them.

When you feel yourself freezing, move. Don’t wait for clarity that never comes.

Reflection

I still struggle with time management. I probably always will to some degree. But I’ve started to accept that this isn’t about being perfect. It’s about being functional.

Writing this has helped me understand that my time trouble isn’t laziness or stupidity. It’s fear. Fear of being wrong, fear of losing control, fear of not being able to recover.

Next time I catch myself thinking too long in a quiet position, I’ll remind myself of the Midwest Class Championship. I had the game in hand. I just didn’t move.

If you see me at a tournament and I’m staring too long at move 10 in a symmetrical English, feel free to yell “MOVE!” across the room. I’ll probably thank you later.

🔒 For Paid Subscribers

If you’ve made it this far, you’re probably a fellow time trouble addict. To make this post more practical, I’ve created a “Time Management Audit” for paid subscribers. It’s a practical, fillable guide that helps you pinpoint exactly why you fall into time trouble, and what to do about it.

Inside, you’ll map your emotional triggers, build personalized coping plans, and create a 30-day system for rebuilding clock confidence.

Paid subscribers can download it instantly below. Use it after your next tournament, or even after your next online session, to turn awareness into real progress.

In addition, you’ll get access to the “Chess Improvement Tracker” found in this post:

And the “Self Analysis Template” found in this post:

👉 Upgrade to a paid subscription to get your copy of the Time Management Audit PDF and start mastering your clock today.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Chess Chatter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.