Today was the final day for the King’s Island Open tournament in Ohio. I did not play in this tournament myself but I wanted to show how I would have prepared for a specific opponent if I had played in the tournament. In this blog post I’ll be detailing the process for how I prepare for opponent’s at my (master-plus) level. This way of preparing for opponents might be different from how other players at (or above) my level would do things but this is my personal method of doing things. Maybe you’ll be able to take something away from this post that will help you to prepare for your future opponents.

Disclaimer: Not all of the things I mention in this post will be able to be done by all players. This is for a few reasons: 1. You may play a narrow opening repertoire and not be as flexible in adapting to your opponent’s openings 2. The lower-rated your opponent is, the more difficult it will be to find their games/opening statistics online.

Ok, so let’s imagine we came up against Grandmaster Mikhail Antipov at some point in the tournament (he ended up winning clear first place) and needed to prepare to play against him. Where do we start?

Well, first of all, this depends on what color we have. Let’s go with the assumption that we’ll be White in this upcoming game. What do we do with this information?

Step 1: Download Opponent’s Games

The first thing we need to do is download our opponent’s games and see what their opening repertoire looks like. I usually do this in two main ways:

Go to players.chessbase.com and download their recent games (most useful for higher-rated players that ChessBase tracks)

Go to openingtree.com and look up our opponent’s online games (useful for all rating levels if you know what your opponent’s online username is)

Let’s focus on the first option. We start by going to players.chessbase.com:

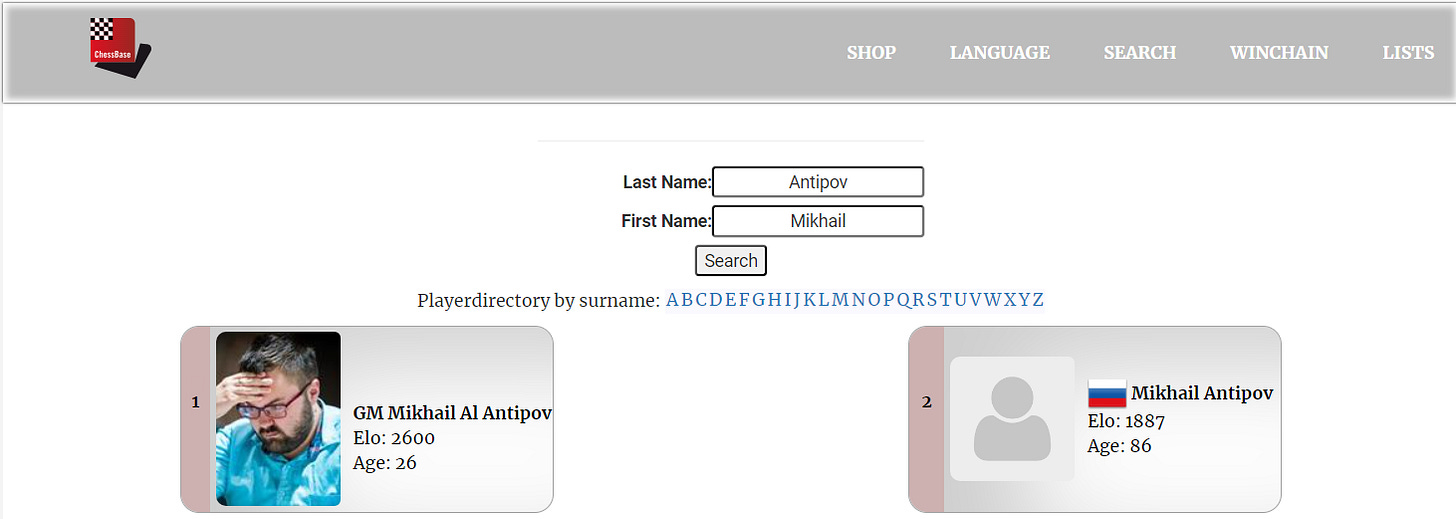

Next we click on “search” in the navigation bar and type in our opponent’s name:

Now we click on their name in the search results and scroll down to the “Download” option at the bottom of the page (red circle in the screenshot):

A small list will pop up and then I select “Download & Copy - PGN”. Once I’ve done this then a ChessBase file will be downloaded into my computer’s download folder. I open it up and see this:

What I have just downloaded is the 100 most recent games of my opponent that ChessBase has tracked. This includes over-the-board tournament games as well as relatively important online games (Titled Tuesday, AI Cup, etc.) This list of games does NOT include random, non-tournament online games that this opponent has played. That is what openingtree.com is for (more details on this in a future blog post).

In my specific case here, the 100 games of Antipov have been downloaded to the “MyPGNDownloads” file which includes a ton of other random games that I’ve downloaded in the past. I need to extract these 100 games and put them in a separate file. To do that, I select the 100 games and then right-click → “Output” → “Database” which creates a new database with only the 100 selected games. I’ll title the database “Mikhail Antipov”:

Now we finally have a database of Antipov’s 100 most recent important games. There will be close to 50 White games and 50 Black games.

Step 2: Create Opening Tree

Now that we have the 100-game database, we need to see how the opening tree looks. Since we’re going to be playing White in this game, we need to select all of the games that Antipov played as Black.

First we click on “Black” in the name filter which will order all the games in alphabetical order by black’s last name:

Then we select the 50ish games that Antipov played as Black. Finally, we can use a keyboard shortcut to bring up the opening tree. Once the 50 48 games are selected then we do Shift+Enter to create the opening tree:

Finally we have the opening tree for Antipov’s games where he played Black. You can see the first move of the game in the list to the right of the board. The “N” column is the number of games that were played with the move next to it. The “%” column is the percentage score that White has achieved using the move in the row. The “Av” column is the average rating of the player who played that move. The “Perf” column is the performance rating of the players who played the move in the row.

Step 3: Analyze Statistics

What can we gather from these statistics? If we’re purely focusing on the first move of the game for now, it looks like 1. e4 is the statistically-best move for White (which is the color we’re playing in our hypothetical game) against Antipov by a big margin. It has the highest number of games (biggest sample size), a strong score for White (60.4%) and the performance rating of the players who go for 1. e4 against Antipov is about 150 points higher than the players actual rating average (2660 vs 2515)! Assuming that we have the ability to play 1. e4 in our opening repertoire, it seems like this would be good starting choice for us to play against him. Thankfully, I can play 1. e4, 1. d4, 1. Nf3 and 1. c4 all with a good comfort level. Now, just because we play 1. e4, does that mean we are guaranteed to win the game? Of course not. But, it looks like he is not as comfortable against 1. e4 for whatever reason (which we may find our later). This is especially in comparison to 1. d4 where White scores an abysmal 32.1% and the performance rating of the players is lower than the average rating (though, not by much).

Ok, so we’re going to play 1. e4 in this game. What will he respond with?

It looks like Antipov has two options that he can play aginst 1. e4. He can respond with 1…e5 or the Sicilian. Note that White scores much better against his 1…e5 response (71.4%) compared to white’s score against his Sicilian (45%). Another tricky thing here is that he plays both of these moves about the same amount of times. He doesn’t seem to lean towards one over the other too much. A 4-game difference is not much at all. With this in mind, we can do two things: We can try to figure out if it is purely random which move he decides to go with against 1. e4 or if he is playing one specific choice against a specific rating category. It is very common for players to play one particular opening (usually more solid) against similar or higher-rated players while playing a completely different (usually more dynamic) opening against lower-rated players. There are ways to do some extra digging to infer which choice he might play against me in this hypothetical game but I can probably go with a simple assumption that he would play the Sicilian for the main reason of it being a more dynamic opening and me being a lower-rated player (GM vs FM). It tends to be that stronger players go for the dynamic opening so that there are less drawish tendencies in the position, especially if they’re playing against a significantly lower-rated player:

From here we can do a bit more digging into the specific variations that Antipov is likely to play against the Open Sicilian (my opening choice):

We can see that he’s mostly playing 2…e6 Sicilians and some additional digging shows that he tends to end up in Hedgehog-style pawn structures since he is mostly playing the Kan Sicilian with 4…a6 later:

Here we can toy around with the specific variation we want to play and this depends on our own opening repertoire a bit as well. If we dig a bit further, we may actually find an interesting possibility in combination with some database and engine-use:

In the position above (which Antipov reached against Fabiano Caruana earlier this year), we have found a novelty! Caruana played 9. Qe2 and that is the most popular move in the position. However, Stockfish is adamant that 9. Nd5 is MUCH stronger than any other move in the position with a +2 evaluation! Imagine if we got to drop the 9. Nd5!! bomb on Antipov in our game. It is a pretty common motif in these types of positions but it would still make our lifetime chess highlight reel :-)

Step 4: Drilling our Preparation

The fourth step is to drill your opening preparation before the game so that you can remember it during the game better. This can be done with your opening file on ChessBase or using an opening repertoire/course on Chessable. Ideally, our opening choice for the game is not too far removed from our usual opening repertoire. The less familiar you are with your pre-game preparation then the more likely you will be to forget it during the game or simply be unfamiliar with the middlegame positions/structures/plans. This is part of the danger of opening preparation but sometimes the benefit is worth the risk.

Step 5: Play the game!

Finally, we go into the game and play our 1. e4 opening preparation! Will Antipov play into what we’ve prepared or will he deviate earlier in the opening? There’s no way to know for sure. If he does deviate earlier then hopefully we’re well-rounded enough to be fine with the positions that occur in the game even if we hadn’t specifically prepared for them ahead of time. At the end of the day this is one of the biggest battles of opening preparation: Getting your opponent into unfamiliar territory while you still know what you’re doing. Ideally with this preparation we did before the game then we have a better chance of achieving this goal.

Hopefully this guide will help you to prepare for opponents in your own games! In the future I plan on doing a version of this guide using openingtree.com which will probably apply to the club-level players a lot more. However, for this specific blog I wanted to show how I go about doing things against strong players in my own preparation.

Let me know in the comments what you thought of this blog post. Finally, if you enjoyed this post then feel free to subscribe for free to the blog below and share it with your friends :-)

Hi Dalton, a great post. The method was similar to that which I follow but I didn't know about the ChessBase page. However, when I try it the download is mostly multiple copies of the same single game. Even with Nakamura, it only returns 7 different games with the last repeated many times. Is there a way around this ? What I usually do is check the online database from within ChessBase. Does this give the same results ? Adam.